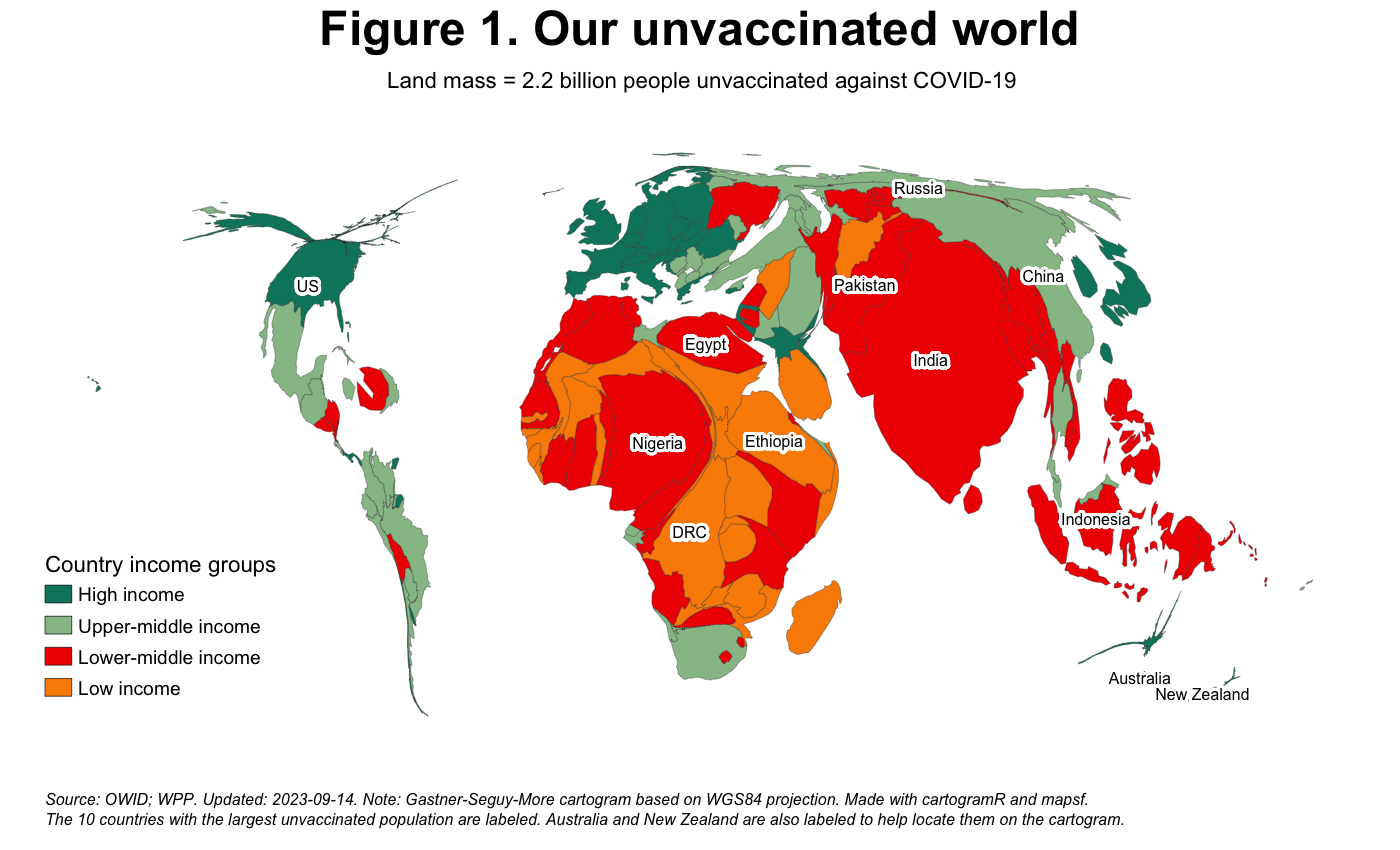

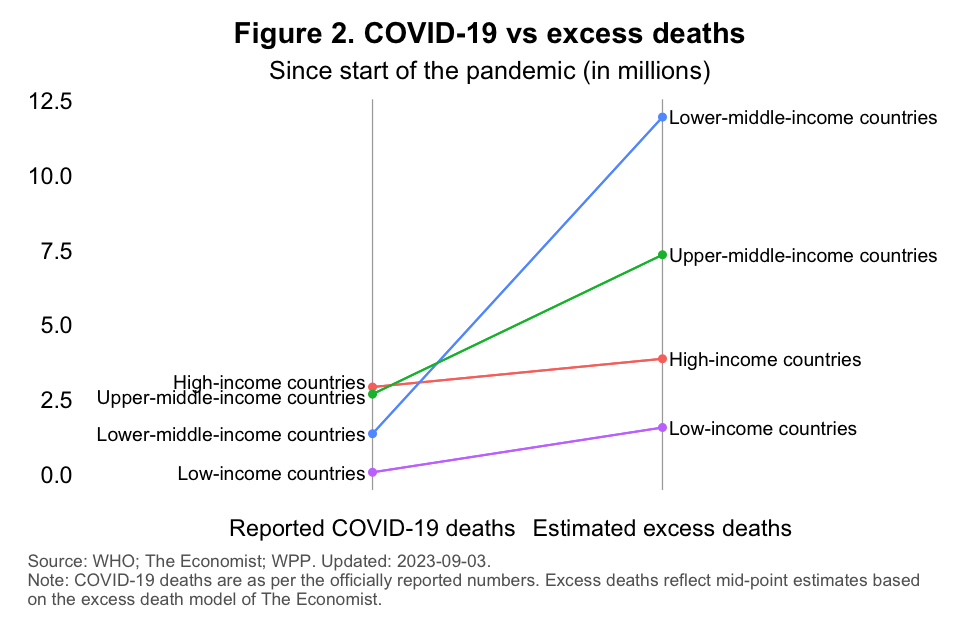

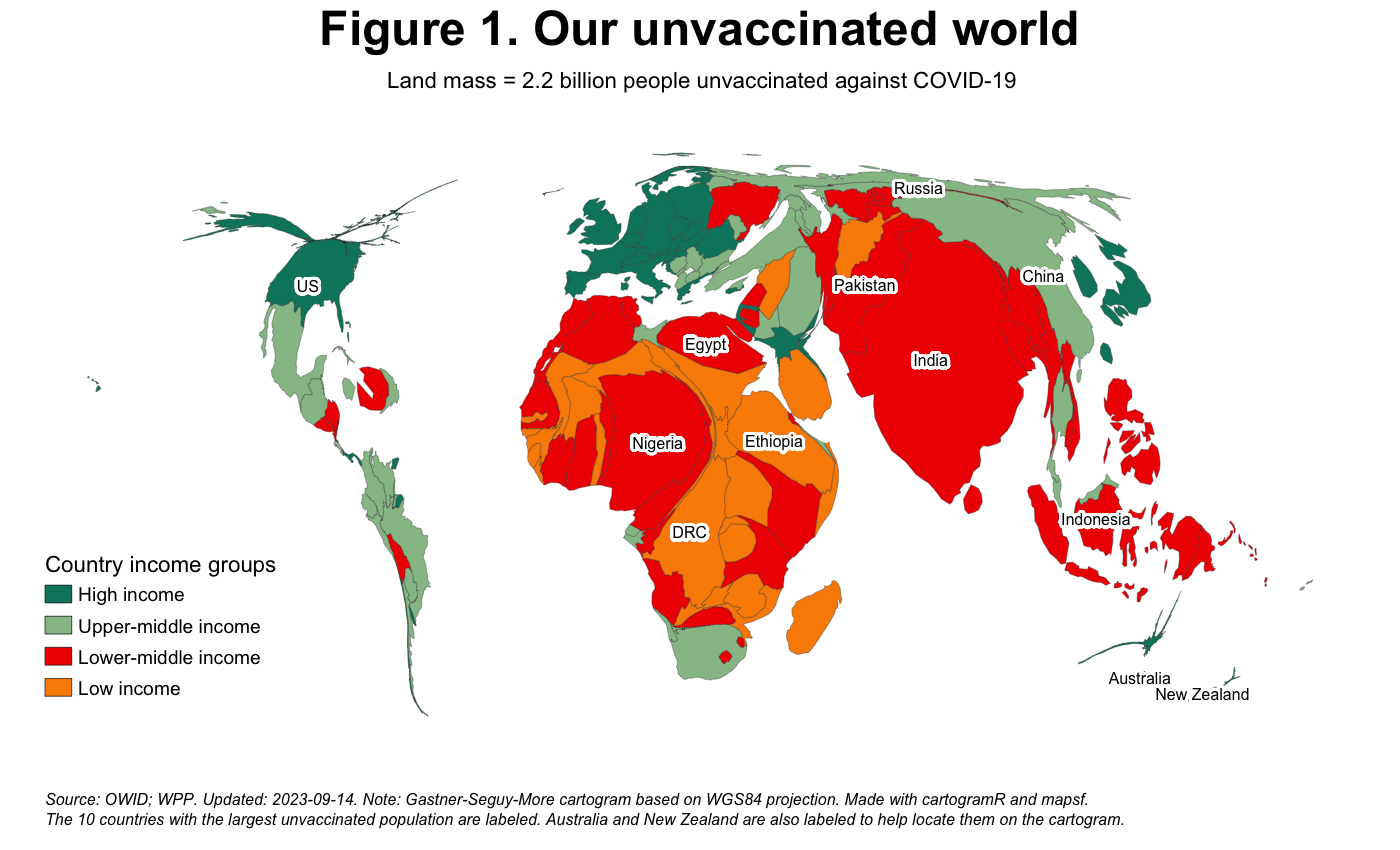

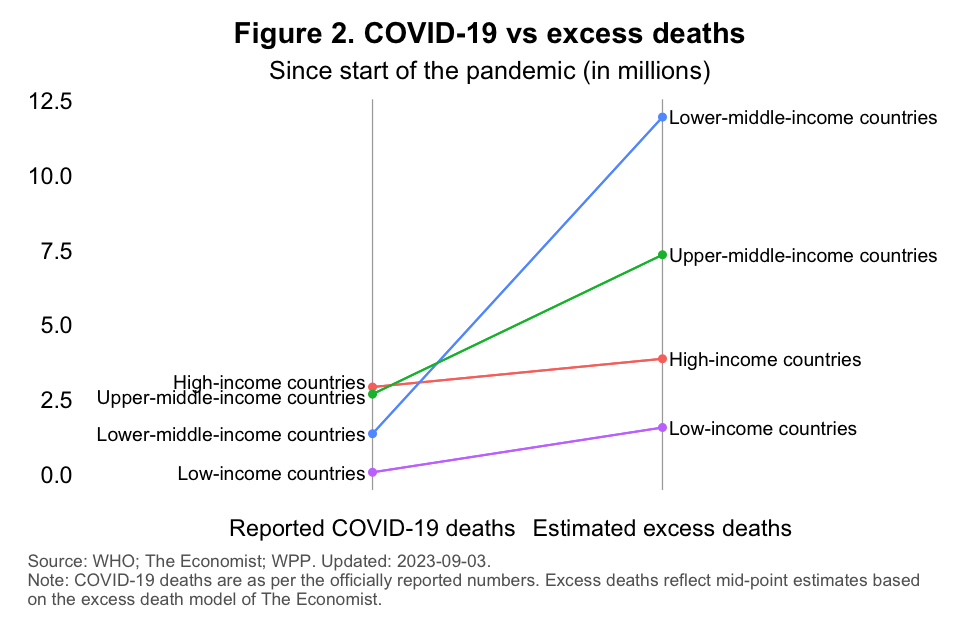

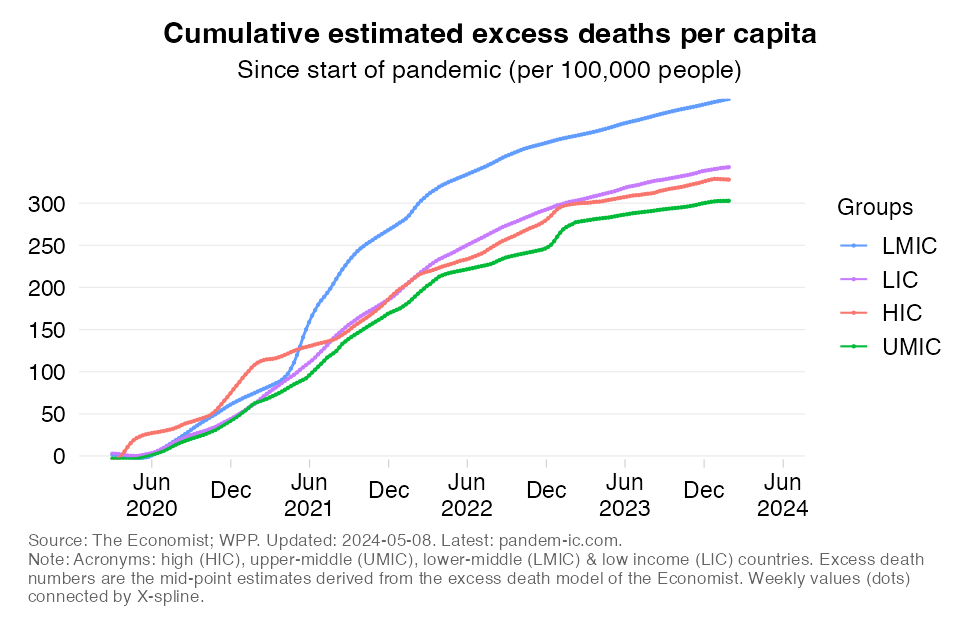

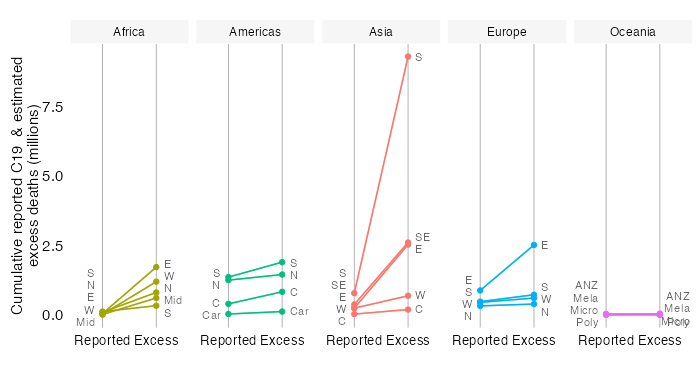

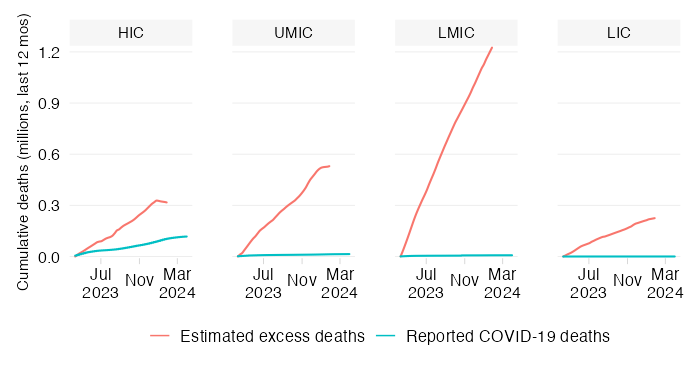

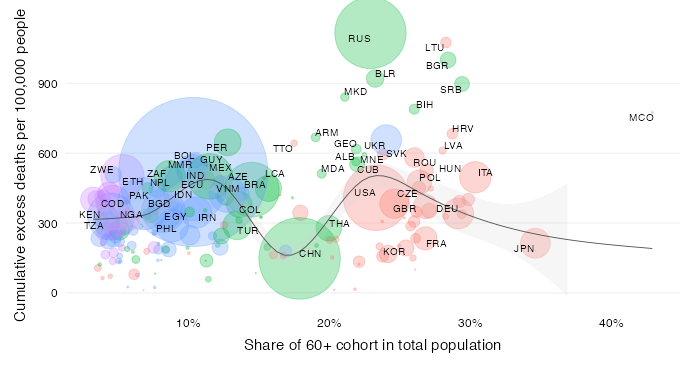

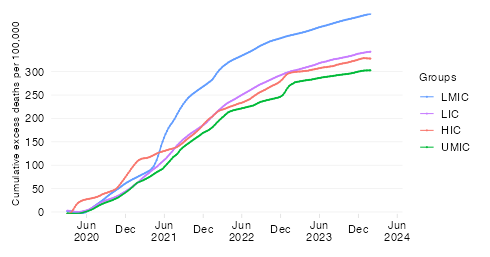

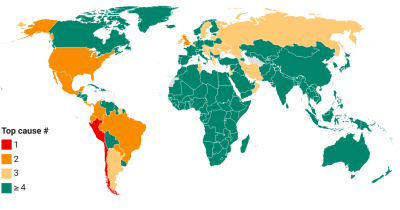

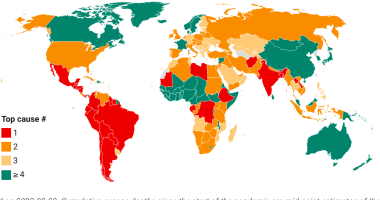

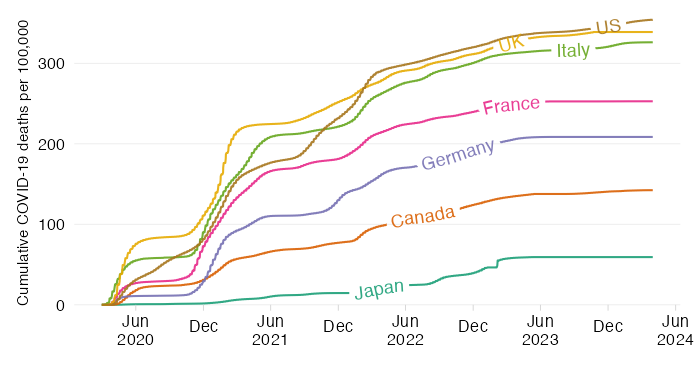

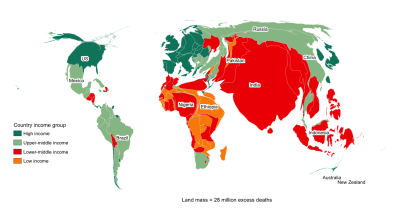

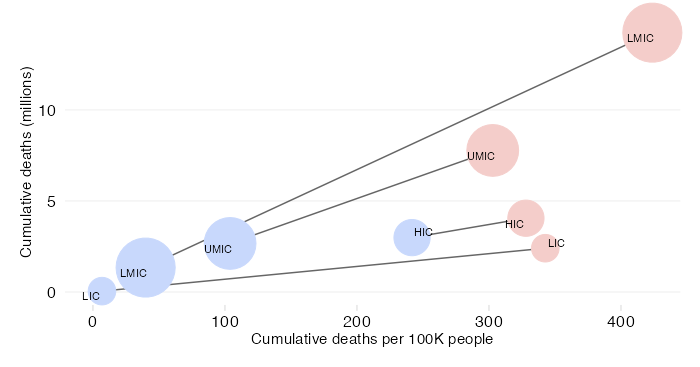

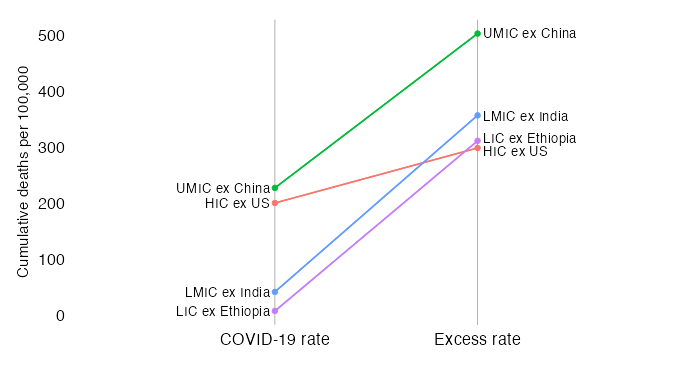

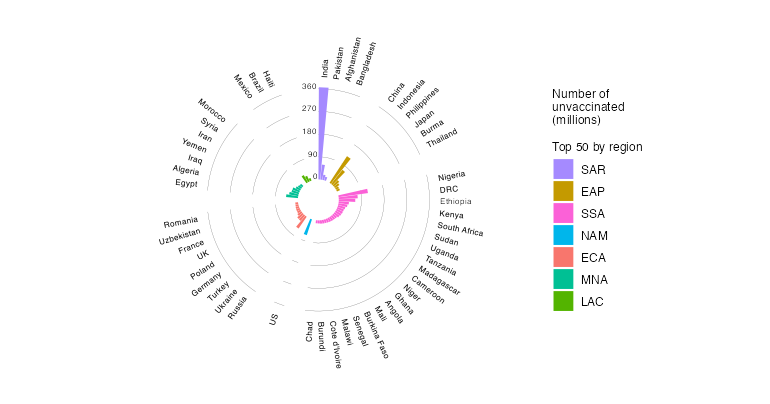

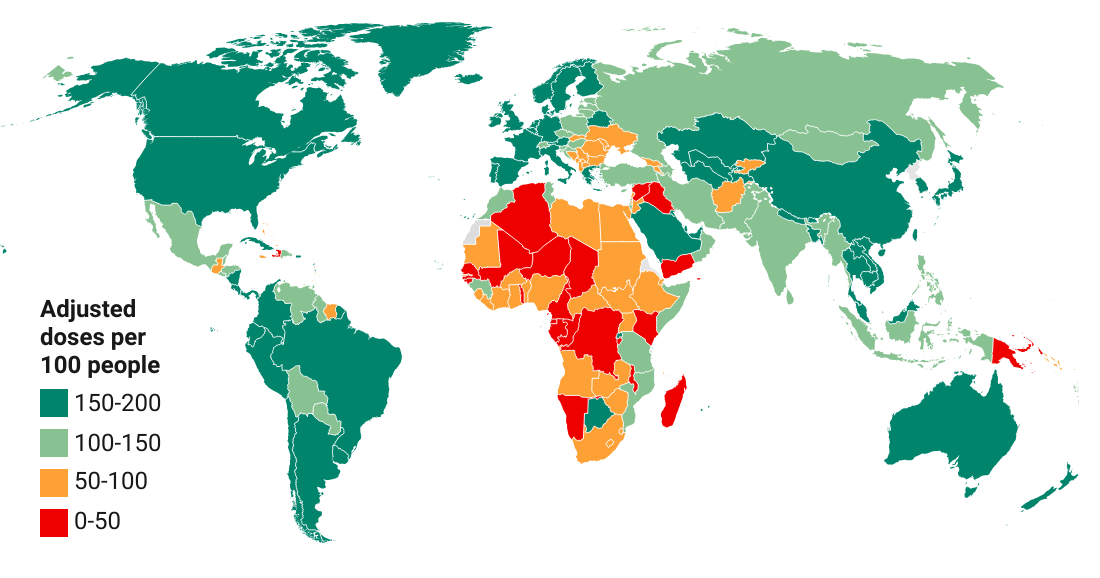

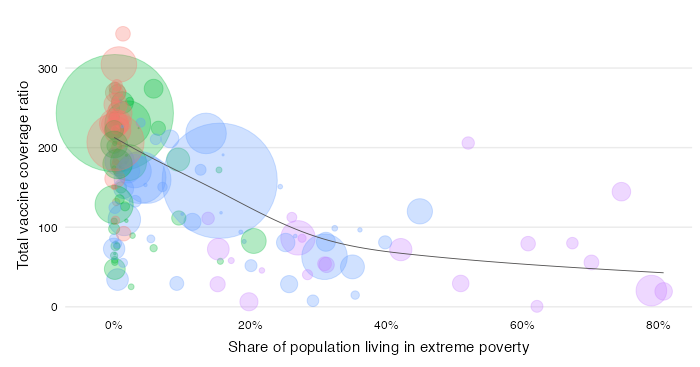

The gripping visuals at pandem-ic are beacons that point to much-needed action. WHO greatly appreciates your dedication and contribution to the pandemic response.

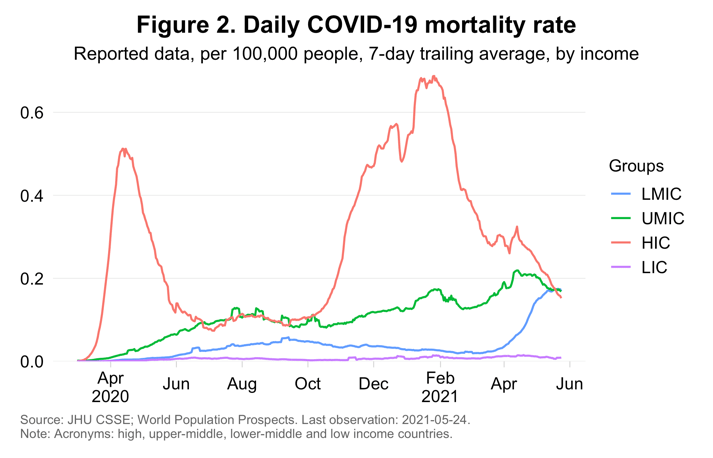

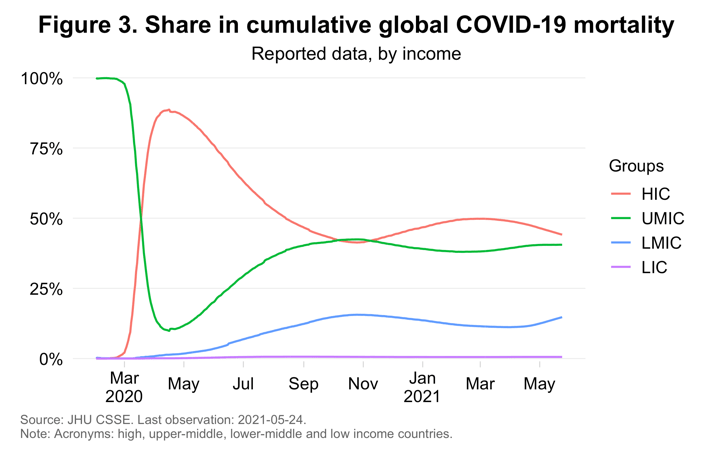

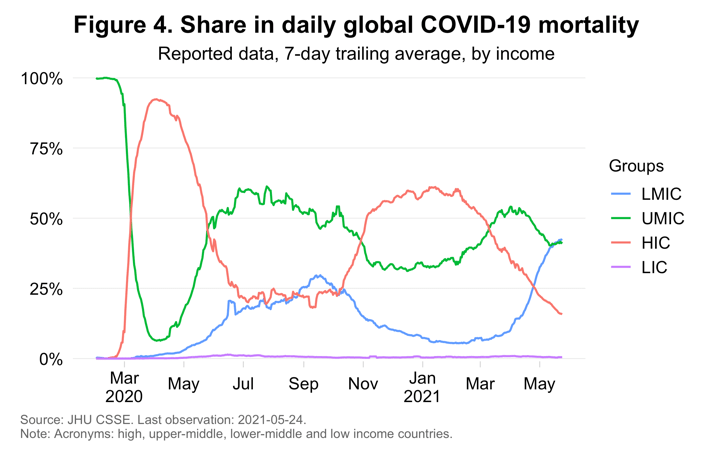

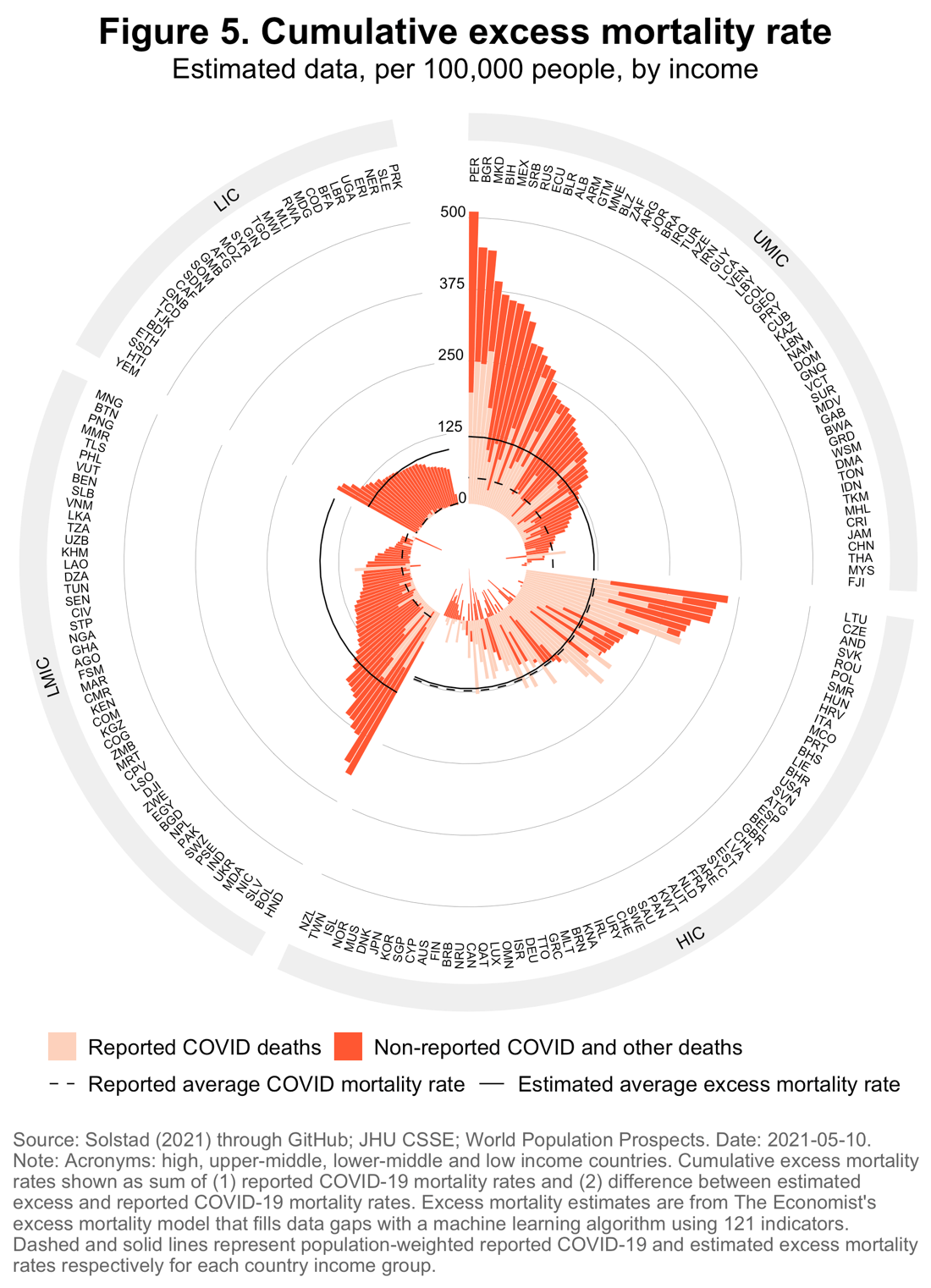

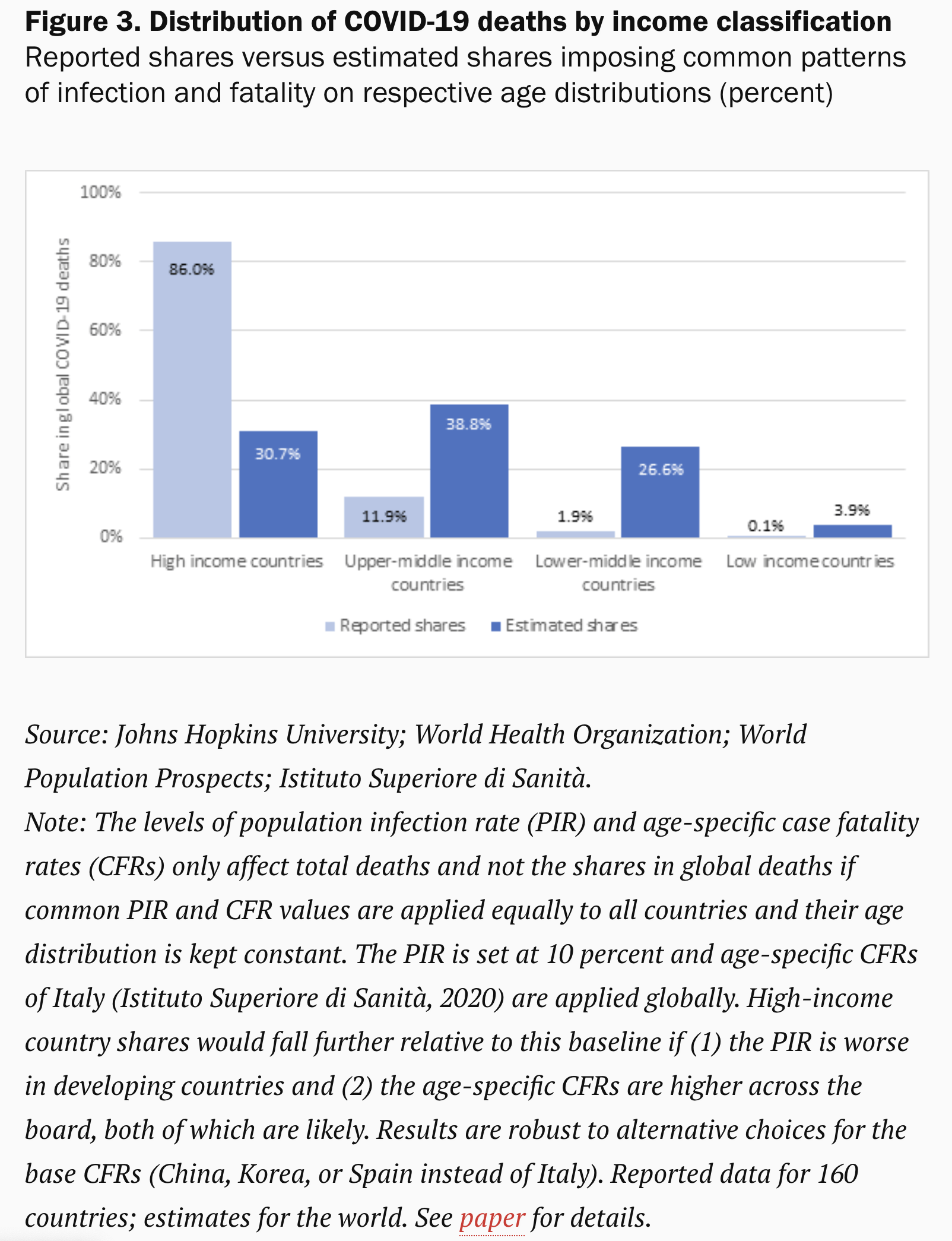

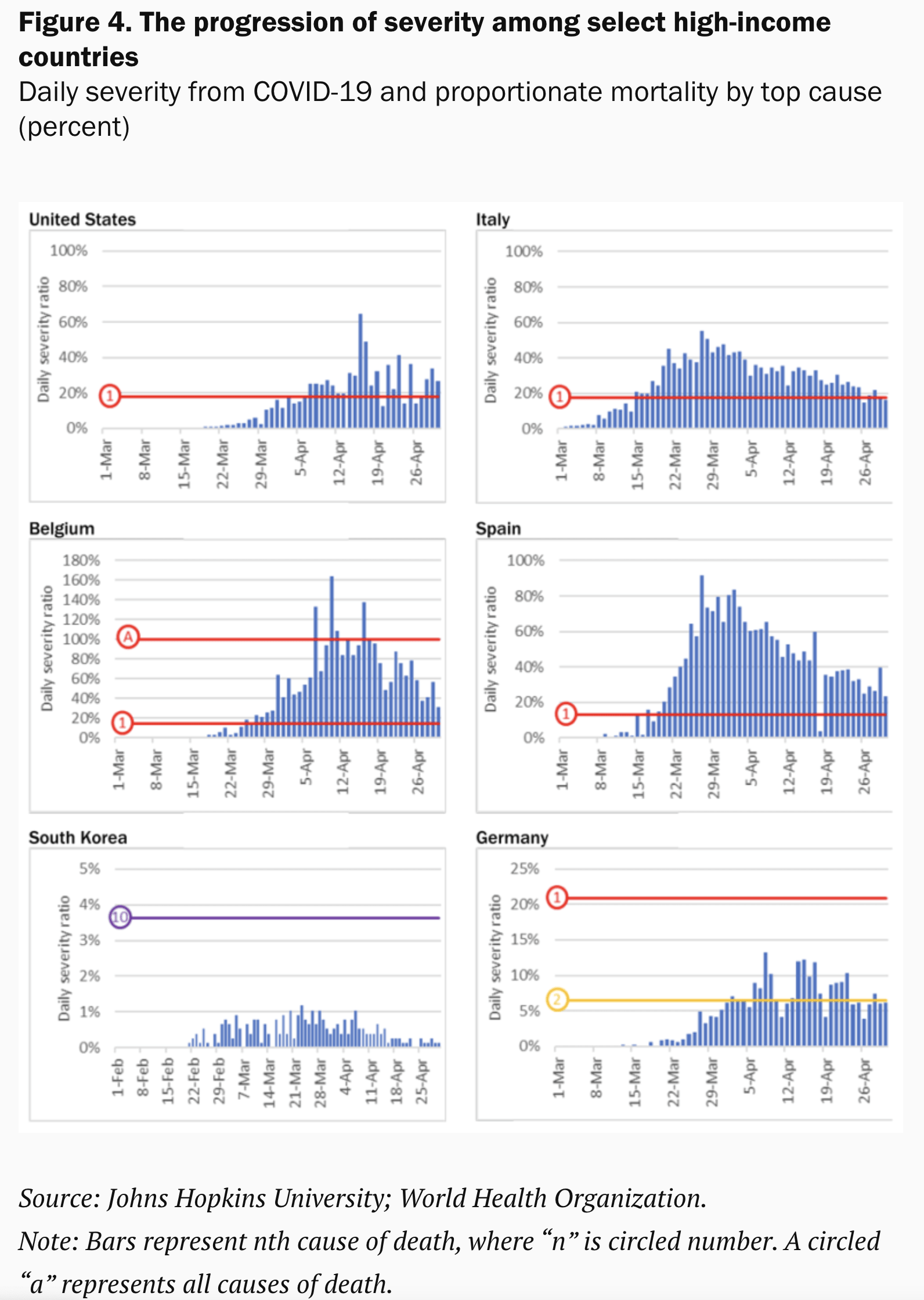

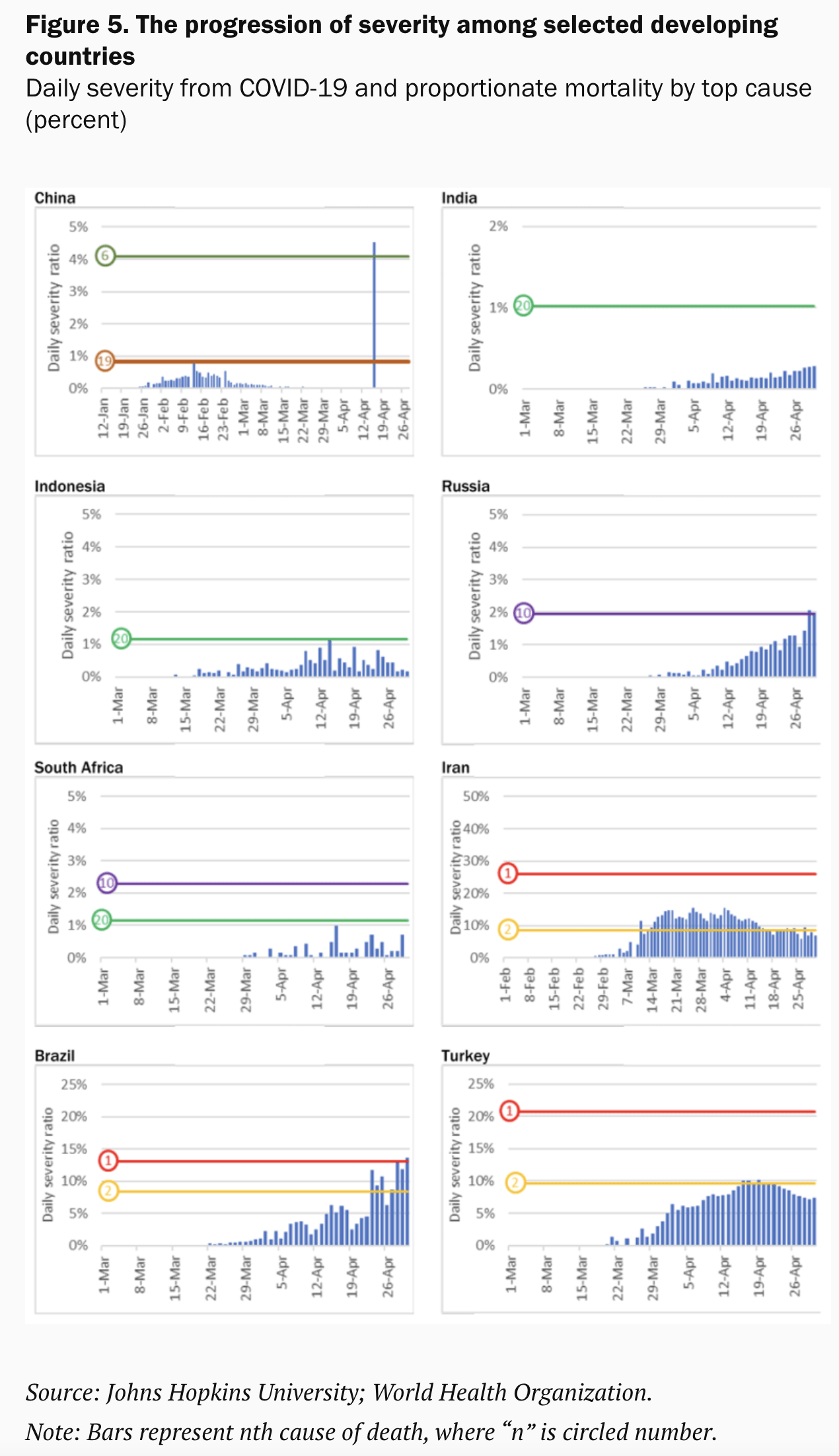

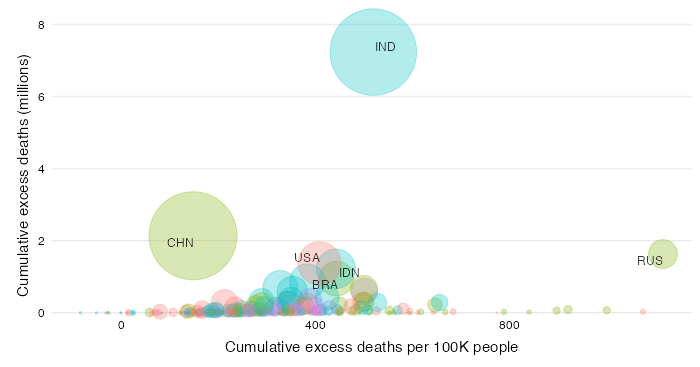

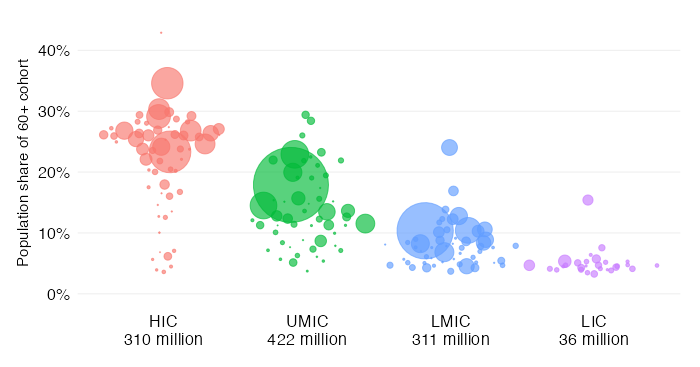

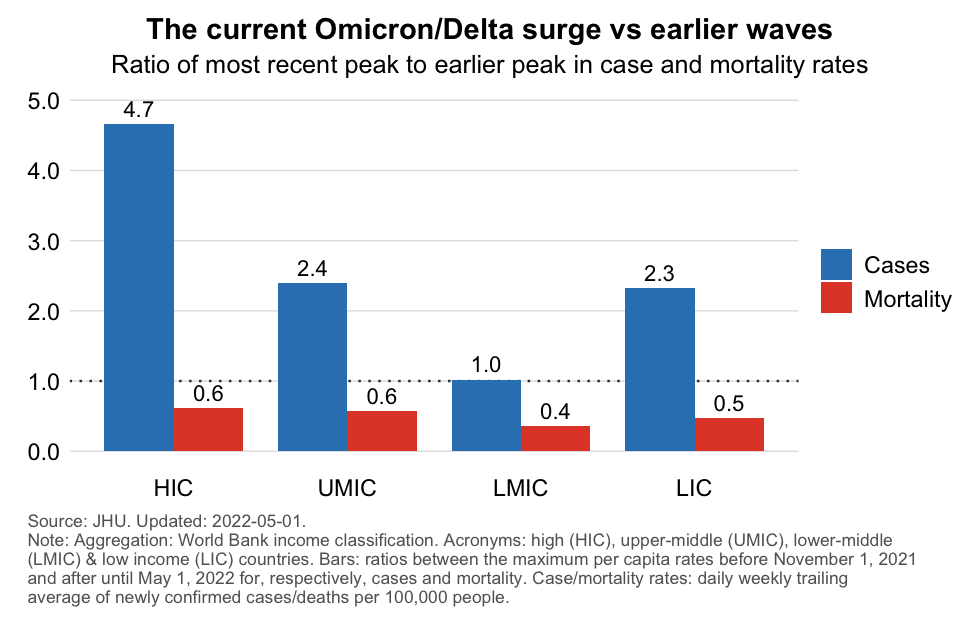

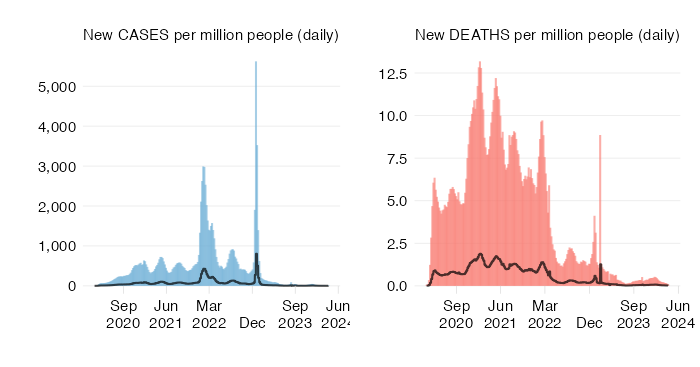

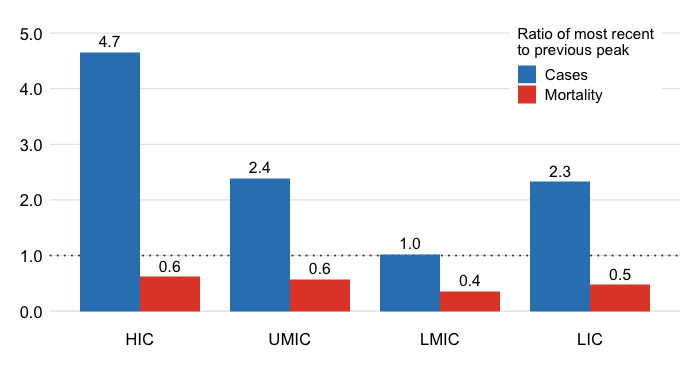

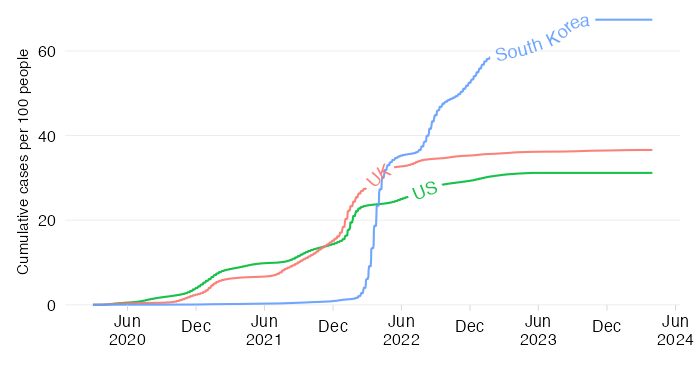

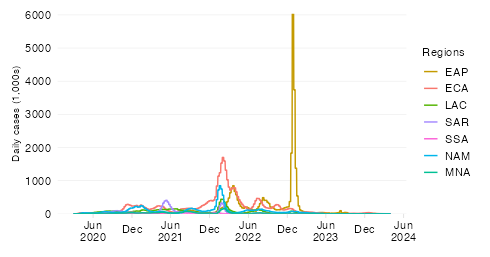

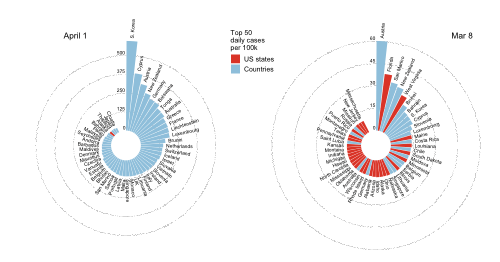

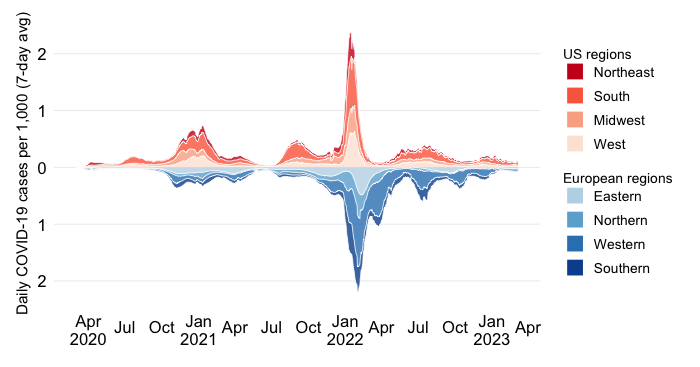

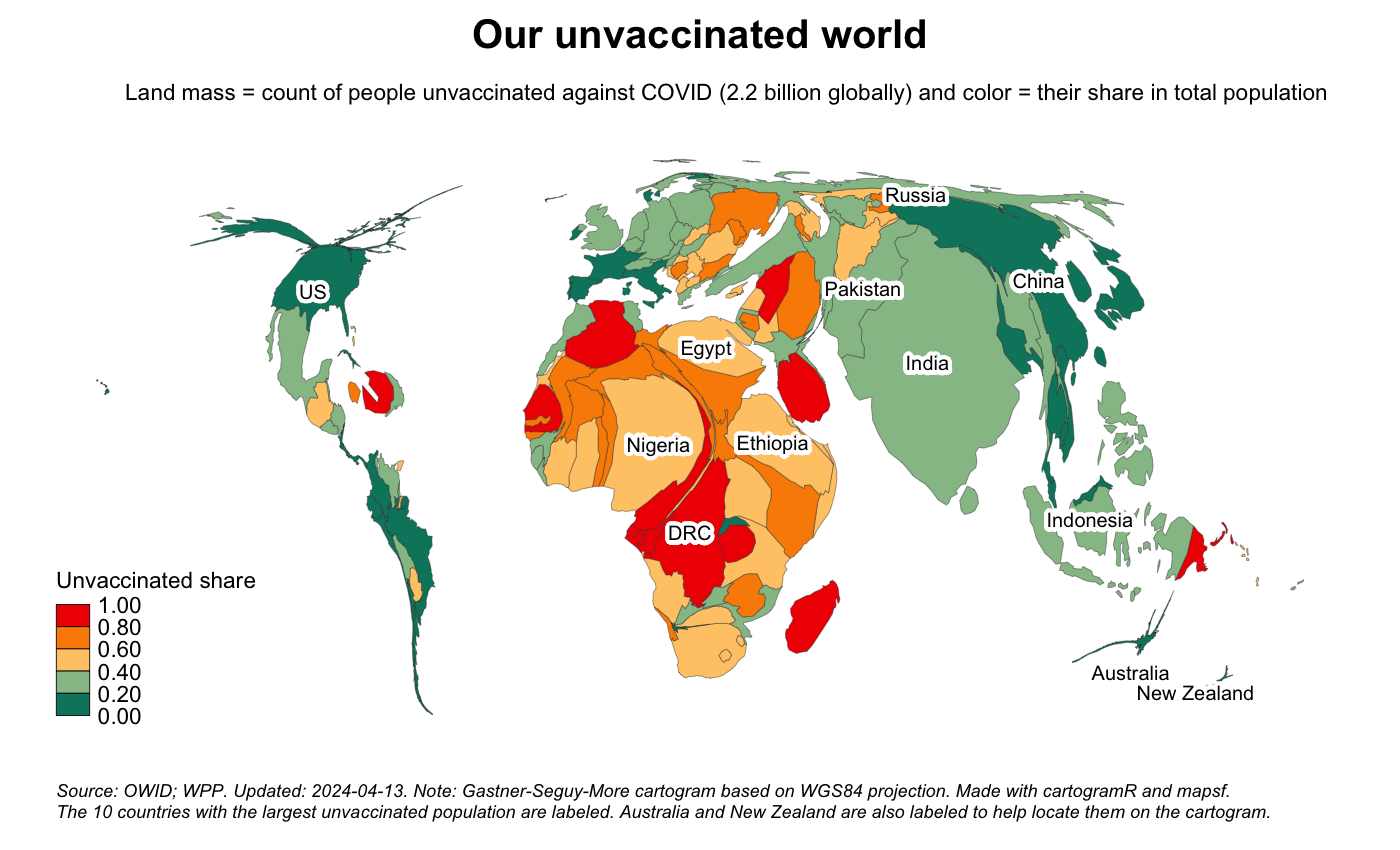

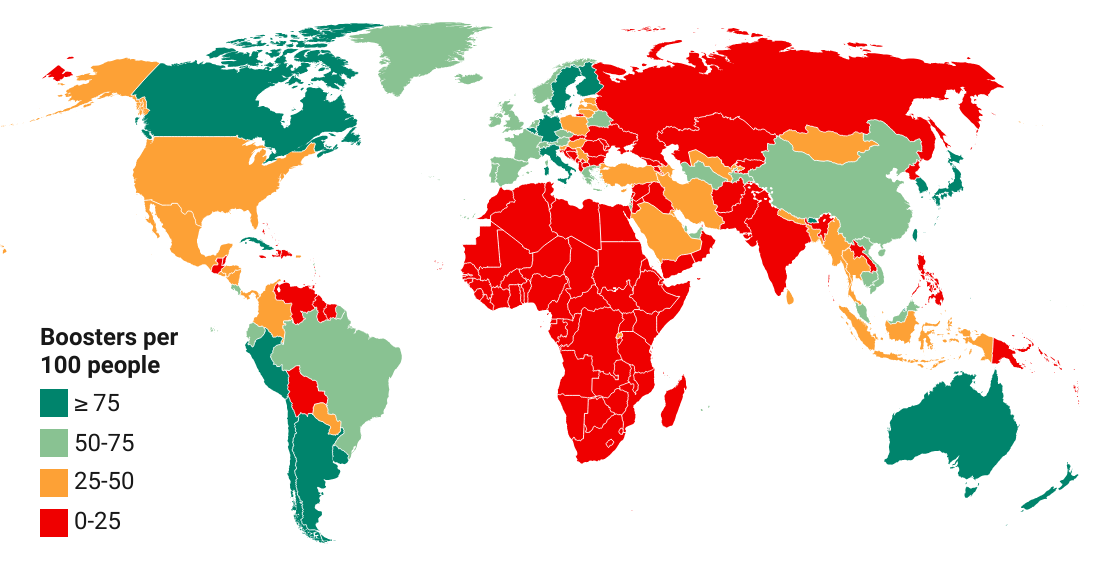

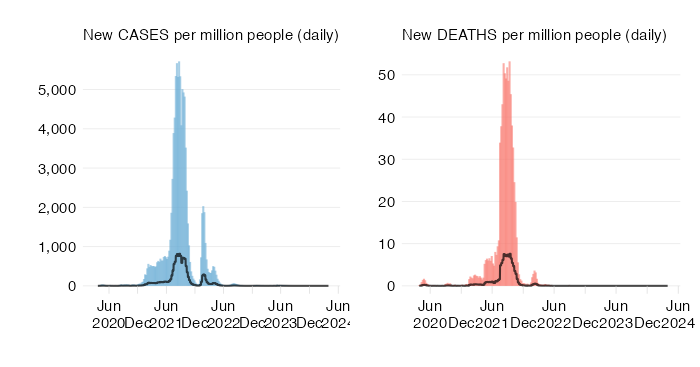

An excellent website visualizing the pandemic and its inequalities

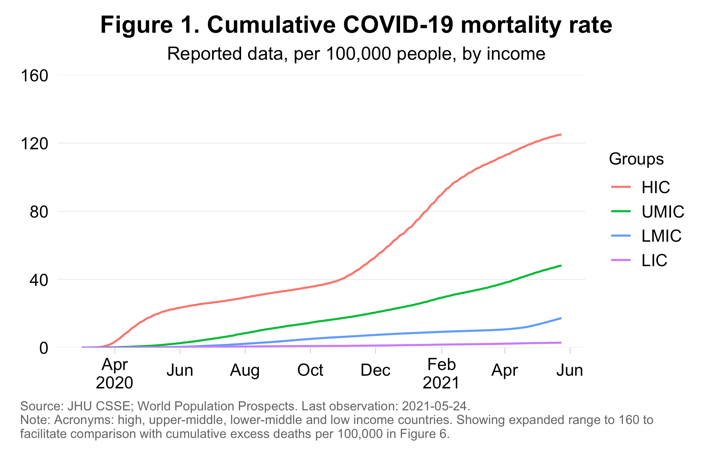

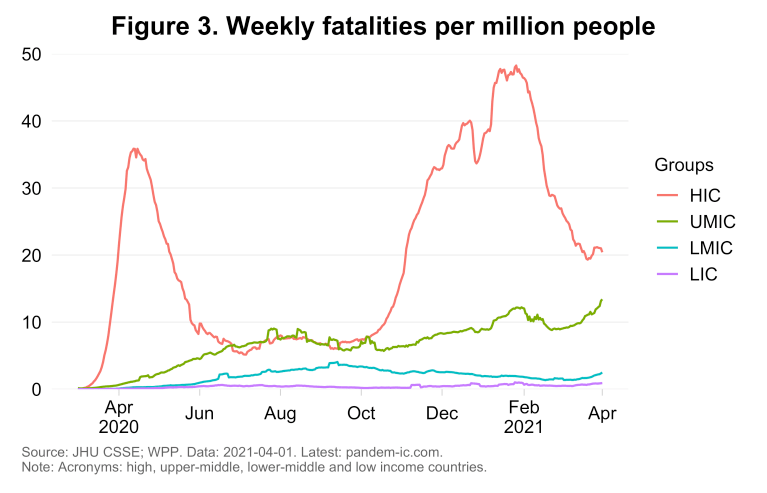

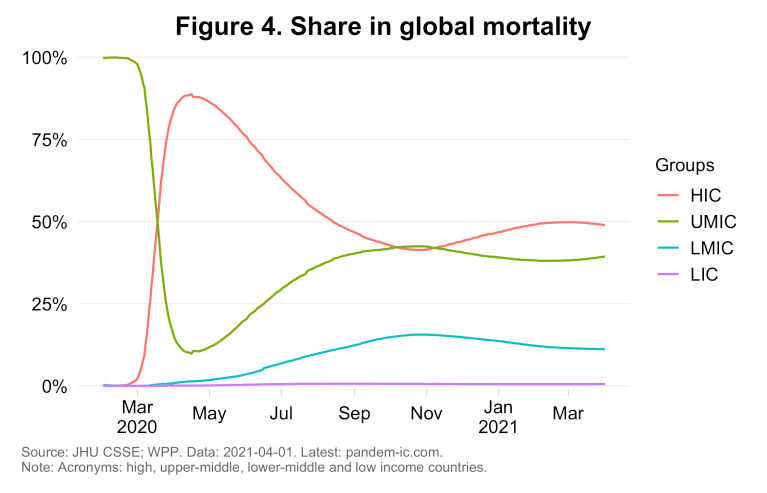

Pandem-ic has been my go-to resource on cases, deaths and vaccinations by country income group - totally vital for policy making and financing

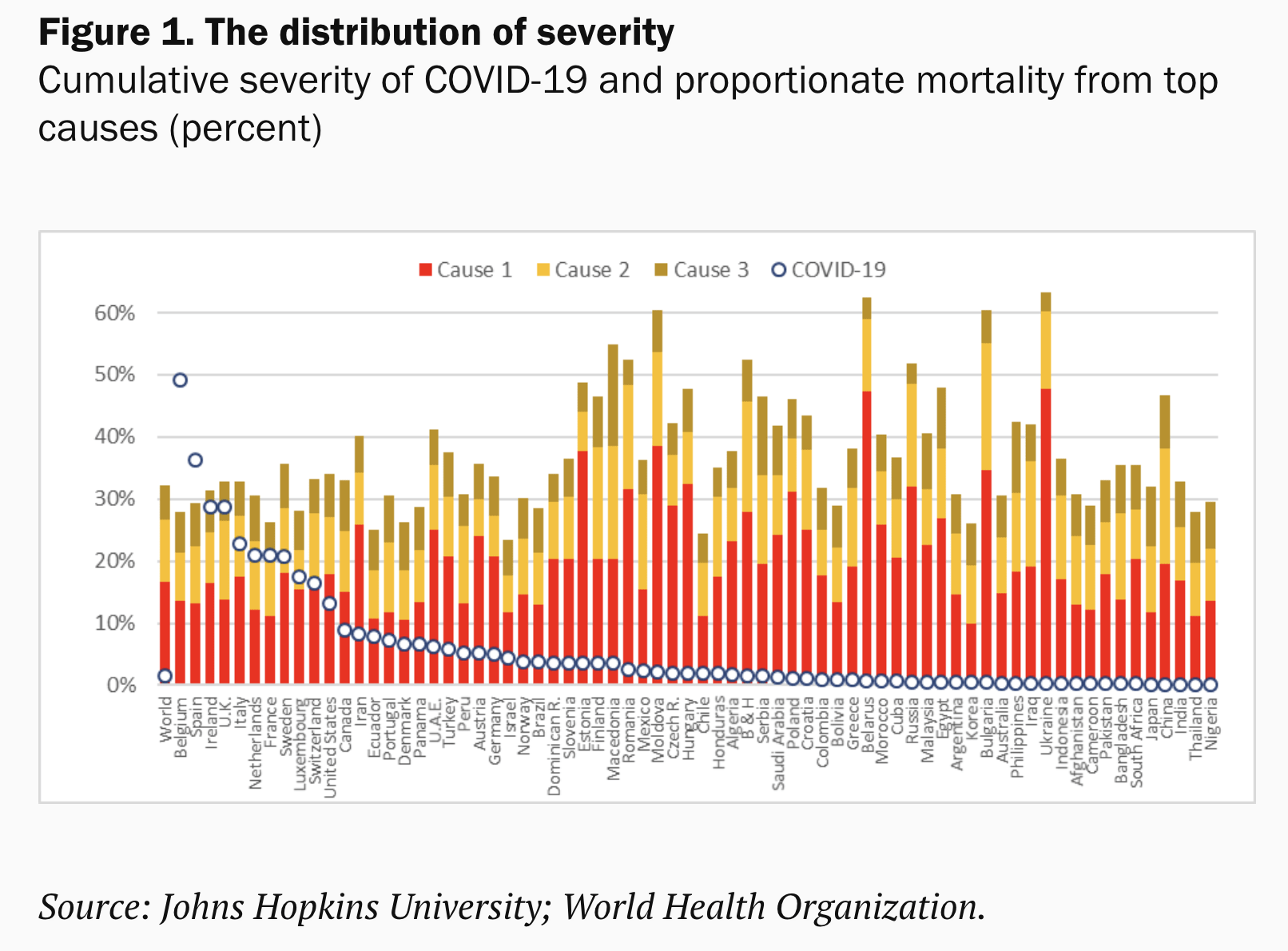

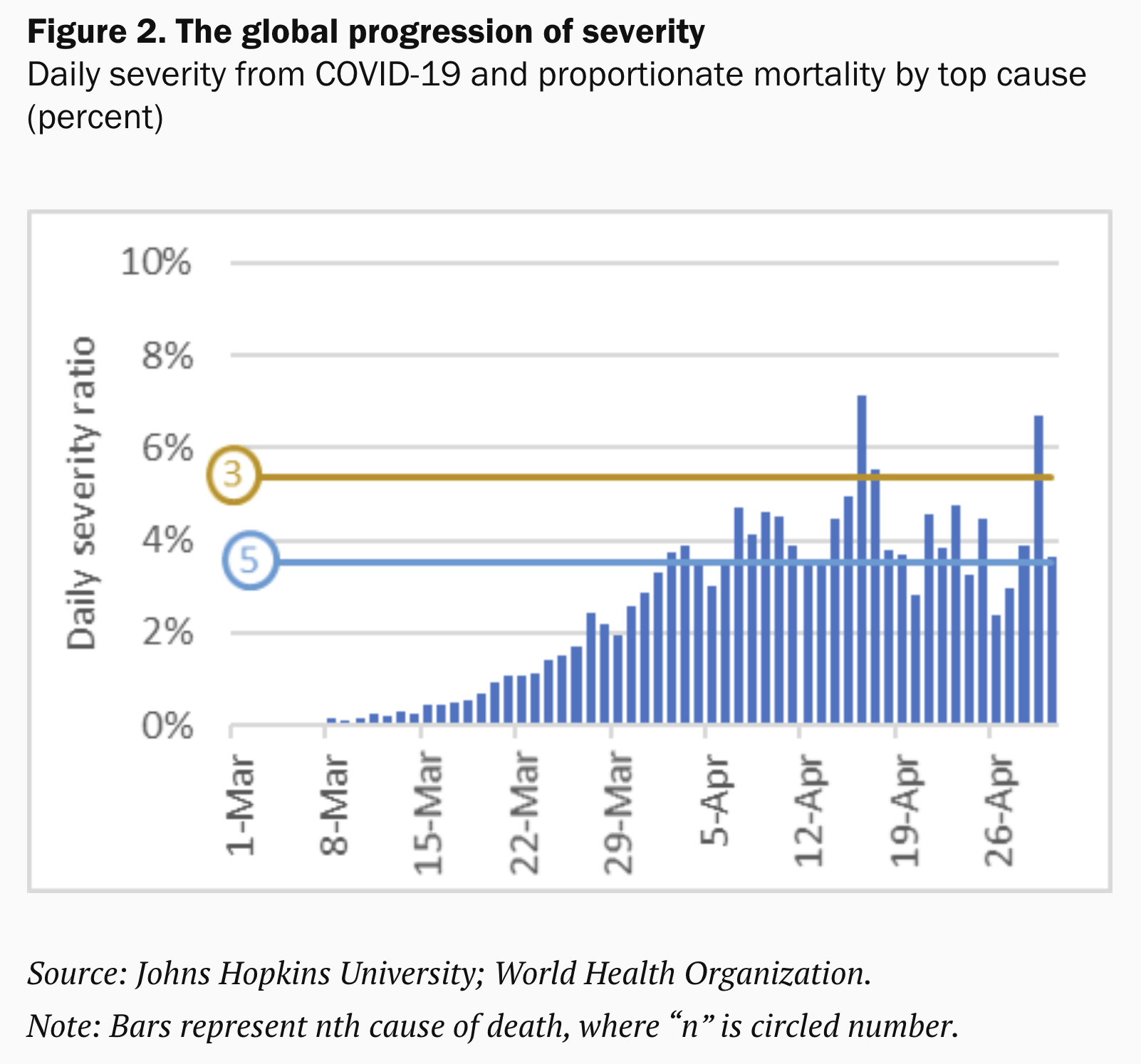

Philip Schellekens is an economist by day, super-hero by night. During this pandemic it has been difficult to find ongoing, reliable information on the pandemic and its global scale; comparative analyses on deaths, infections, vaccinations by regions and countries and; smart, data-driven commentaries on the common misconceptions we have about COVID-19 from coverage of vaccination worldwide to mortality in the developing world. Pandem-ic fills an important gap in keeping us all up-to-date and informed about what matters around the planet during this plague. The fact that it is a labor of love, a volunteer effort, makes Dr. Schellekens a hero in my book. So many people have gone the extra mile (or kilometer) over these past two years to help others and Dr. Schellekens is one of them.

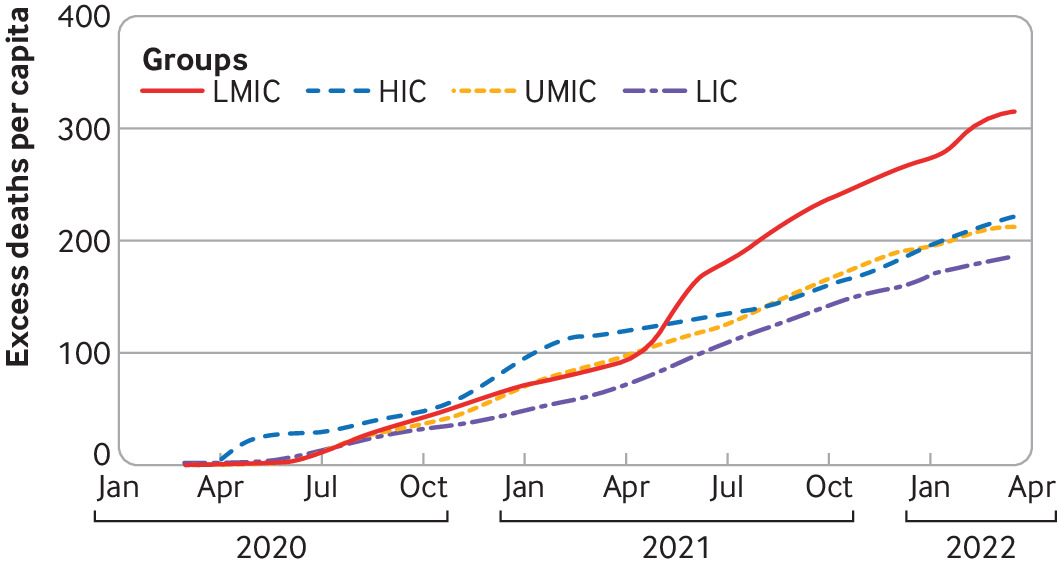

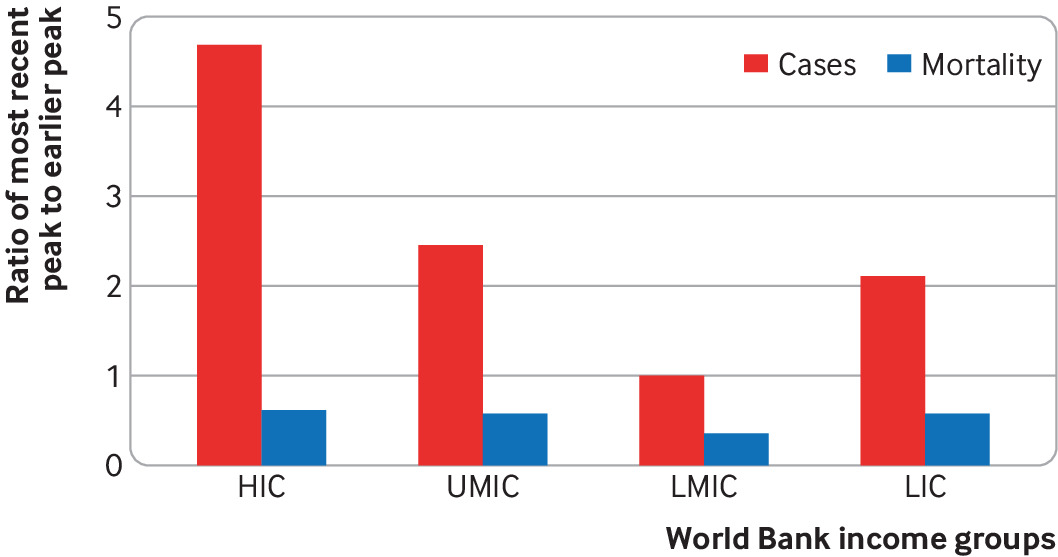

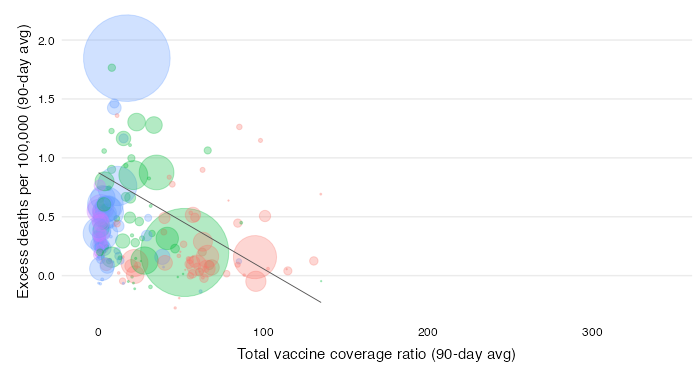

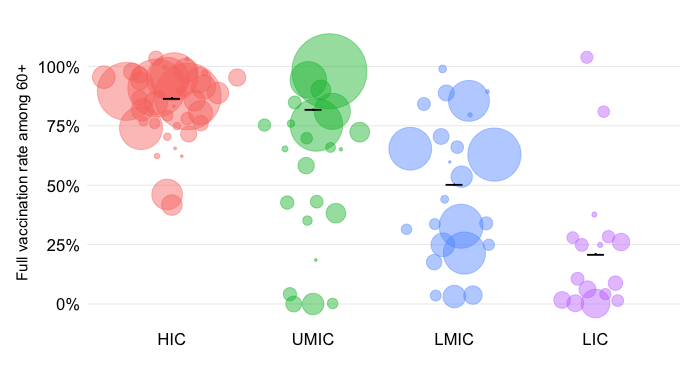

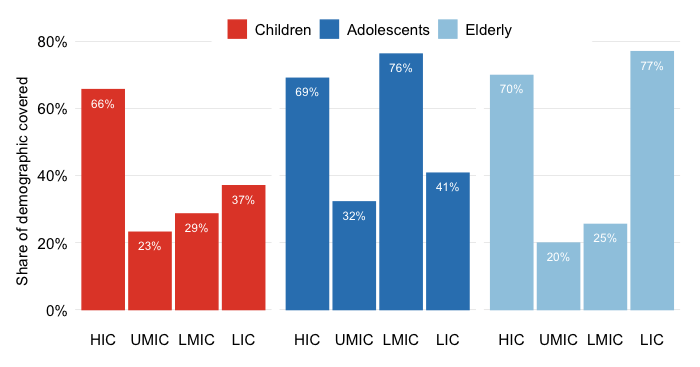

Pandem-ic has been the single most important visualization platform to understand and track global equity during COVID-19. Where a flood of data has so often served to obscure what’s really going on in this pandemic, hiding the stark realities of unequal vaccine access and avoidable mortality, Philip Schellekens has given us a set of tools with which to see the world as it is. Ironically it has become the public good that our vaccine efforts aspire to be. While I hope it is soon made redundant, this work has shown the value of social science in global pandemic response.

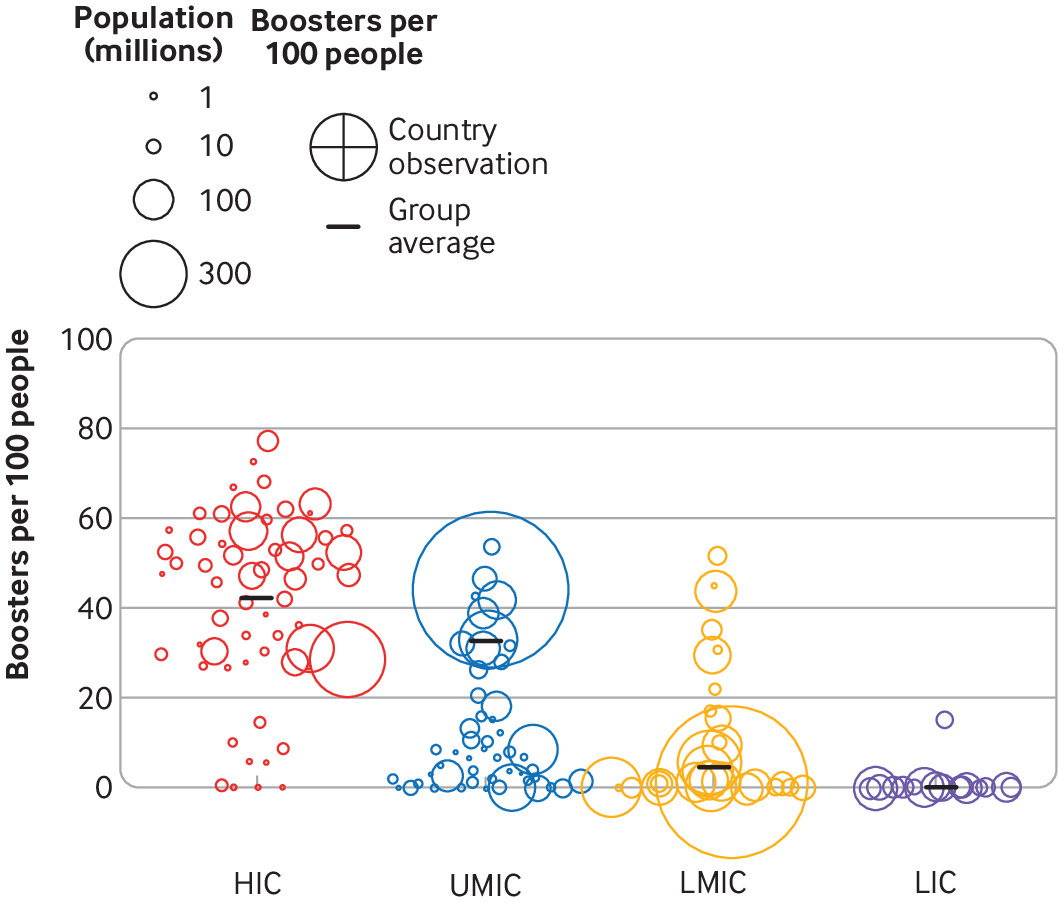

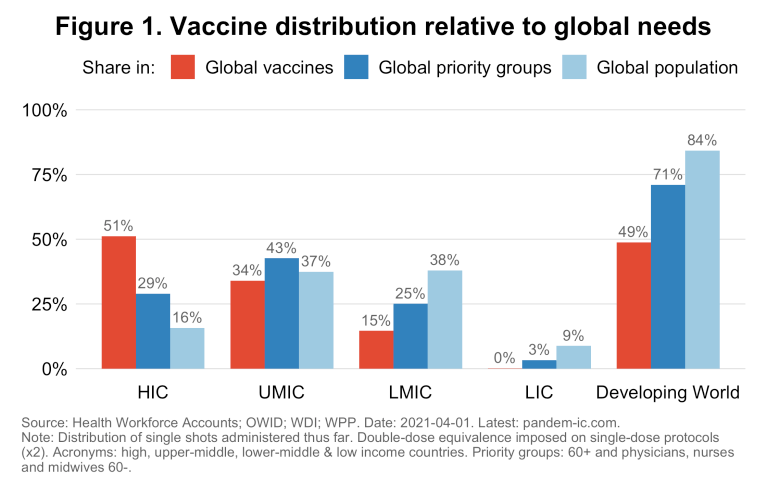

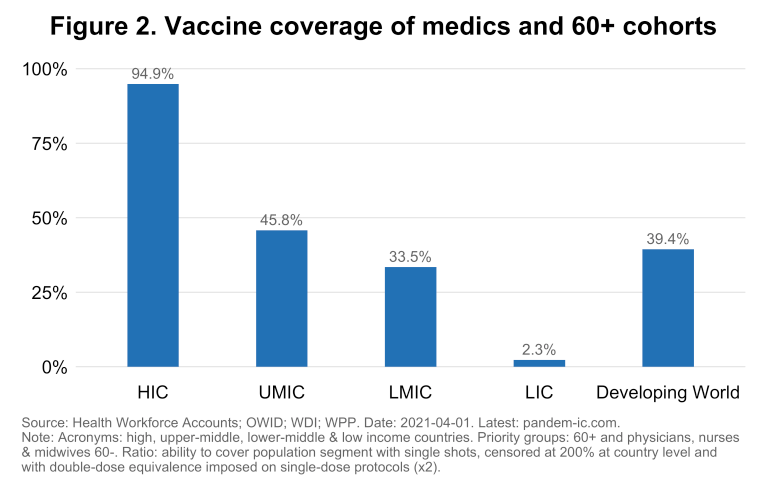

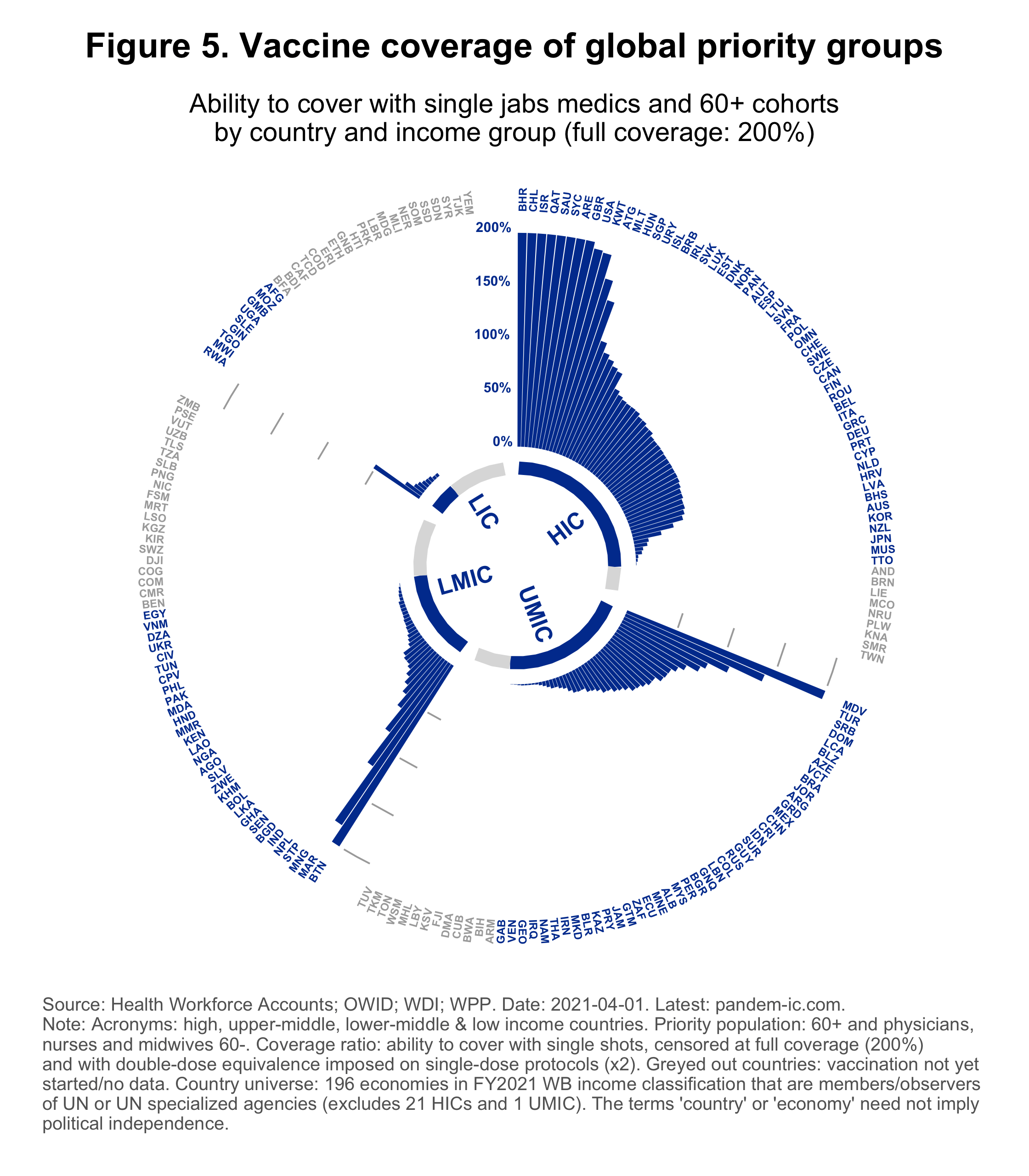

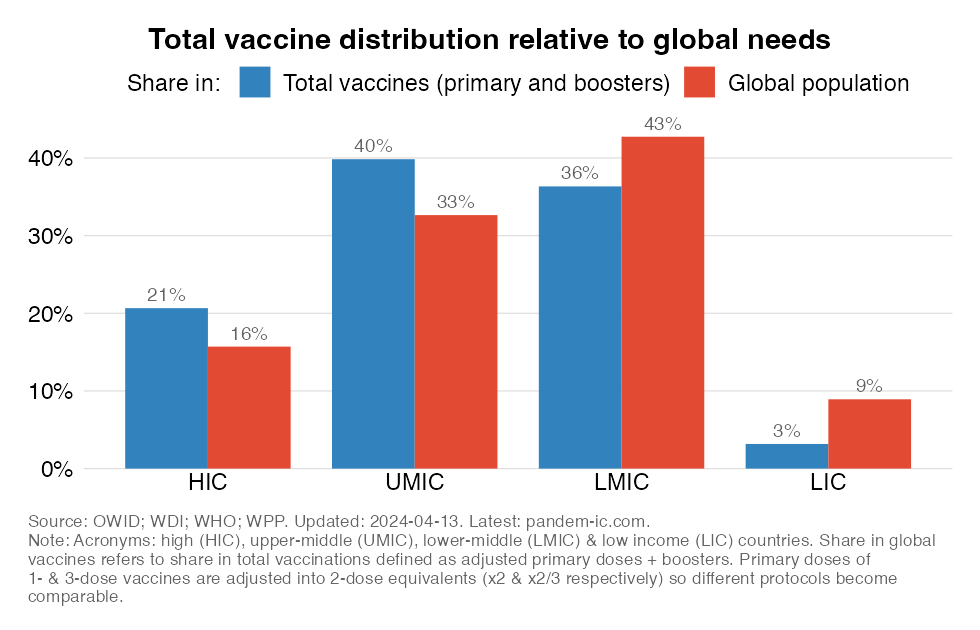

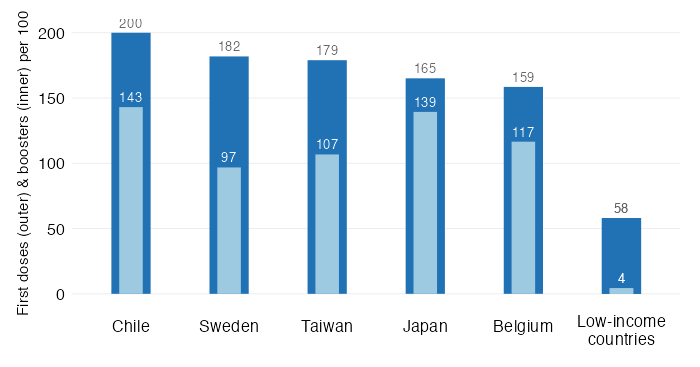

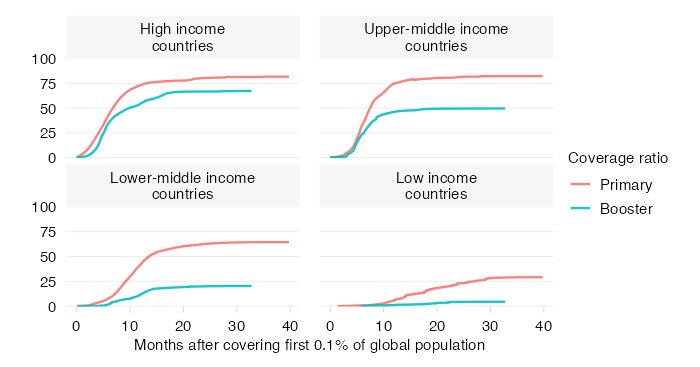

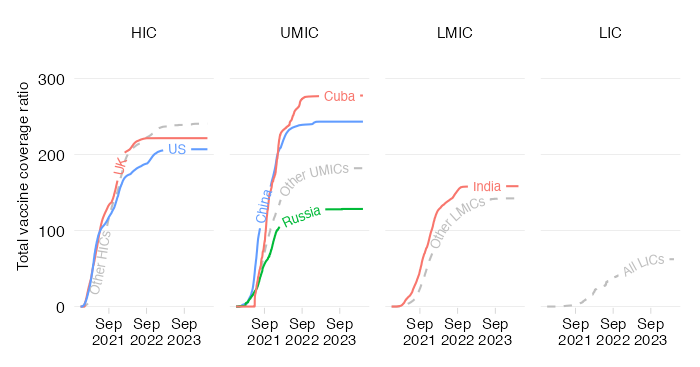

Terrific visualisations that drive home the many aspects of the huge, and continuing, inequality in access to vaccines across country income groups. Important reminder of what remains to be done to bring this pandemic under control.

For those fighting for global vaccine equity, pandem-ic has been an invaluable, easily accessible, frequently updated resource. It has exposed inequities with great clarity and helped raise awareness about what the world needs to do, if we want to end this pandemic

An enormously valuable source of data on the COVID-19 pandemic, exceeding in value the work of many institutions on this topic

Some of the most compelling data analytics on #VaccinEquity

Powerful data visualizations showing the extreme inequities in the global vaccine campaign

Share